I’m writing this post to answer a question I often get: what did I do on God of War: Ragnarök? The short answer is my official title was Associate Systems Designer and I worked on ten side quests, most of the game’s collectibles, and on the banter systems for key side characters like Ratatoskr, Brok, Sindri, and Gna. But the follow up question I get just as often is: what exactly does it mean to work on those things?

Every one of the side quests I worked on had different needs and were in different states of development when I was assigned them. Some were mostly done (“The Elven Sanctum”) and others I took from design document to the state they exist in on the disc today (“Across the Realms”). Additionally, there was a wide variety of side quests. Some were combat-focused (“The Last Remnants of Asgard”), some were puzzle-focused (“The Broken Prison”), some were narrative-focused (“A Stag for All Seasons”), and others were easter eggs (“The Slumbering Trolls.”) But even with this variety of quests, I found myself solving similar problems, even when the goal of the quest differed. So, in this post, I will look at a few of these quests and break down the issues our team faced and how we solved them. My hope is that this post can give you a better idea of how I approach problems as a designer, particularly in a AAA context.

Note: There will be significant spoilers for God of War: Ragnarök throughout this post.

Protecting tone

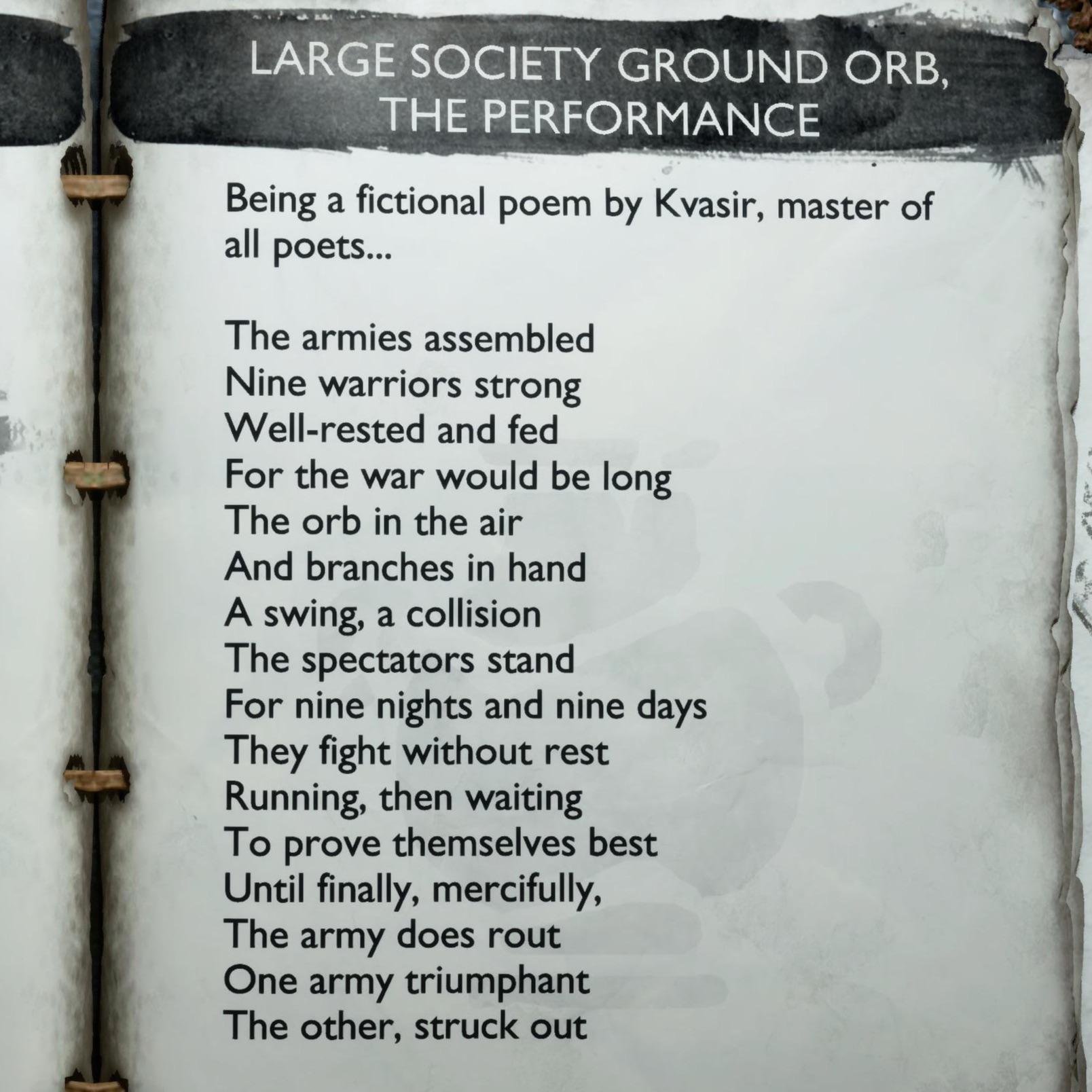

One of my favorite quests that I worked on in Ragnarök was “Kvasir’s Poems.” This was a whimsical collectible set in which each collectible was a book of poetry that made humorous references to other PlayStation games like Ratchet and Clank, Death Stranding, and even MLB: The Show.

The goal with this quest was to support the playful vision for the collectible set while not undercutting the serious tone of Ragnarök as a whole. To make each book feel impactful, I worked with our amazing level design team to find spots for each book that reflected the themes or subject matter of the game it referenced. For example, the Ratchet and Clank book is next to a set of gears in Svartalfheim while the Journey book is initially covered in sand in the Alfheim desert.

The issue with this approach is that sometimes the best spot for a particular collectible might be too close to a key piece of critical path dialogue or the dialogue of another major side quest. For example, the Major League Baseball book was initially supposed to be next to a bar in Nidavellir, the Dwarven capital, but was moved because it was too close to banter that would fire when Atreus and Kratos entered the city for the first time. To avoid these kinds of issues, I had to know the critical path banter and all side quest banter like the back of my hand. I also had to be aware when other side quest or critical path moments were moved or cut, because that could mean that my artifacts were now conflicting with other banter. Sometimes, these cuts would necessitate moves that created a domino-effect where many pieces of banter would need to find a new home. I think hand-programming this banter made it so our characters felt like they were actually reacting to the world around them as opposed to running through a pre-ordained script.

Sometimes there would not be a direct conflict between two bits of side quest content, but the resulting tonal mismatch would be unacceptable. For example, the Journey book of the Kvasir’s Poem collectible set was initially supposed to be near the basement of the Elven Sanctum, where Kratos and his companion would discover a grisly secret murder. The problem is that the Kvasir’s Poems artifacts could trigger humorous banter depending on what order the player picked them up. So while there was no direct banter overlap, putting that book in that spot caused the player to sometimes experience a very dark scene next to a humorous one. To protect the tone of the Elven Sanctum quest, we had to move the book, even though there was not a clear spot for it at the time.

Kratos finds a pile of Elven corpses outside the Elven Sanctum.

Much of the design work I did was this kind of design Sudoku. It was less about finding the best spot for a particular piece of content and more about making sure all the content sang in harmony. One of the mantras that Anthony DiMento, our team’s lead, would repeat to us is that even if 1 in 1000 players encountered a bug or banter conflict, that’s still 1,100 people that will experience it given our huge userbase. Attention to detail was paramount.

Working with narrative

Sometimes, there would be no good place to put a collectible or quest item. For example, one of the tasks I was given during Ragnarök was to place the nine flowers of the “Nine Realms in Bloom” artifact set. The idea behind this set was to put one flower collectible in each of the nine realms. The problem was that at that point in the project, there were no plans for Kratos to be able to freely revisit Jotunheim or Asgard.

The Svartalfheim flower.

We didn’t want to “wave away” this inconsistency by placing these two flowers in a random spot, so the writer Anthony Burch and I brainstormed how we could resolve this issue. We scoured the game for spots where these flowers could exist and the game’s lore for reasons those flowers could exist outside of their parent realm. (At all points in the project, I had several textbooks of Norse and Greek mythology on hand for this kind of research.)

After some research, we discovered two spots. As those who have beaten the game know, the game’s climax is the destruction of Asgard, which causes chunks of Asgard to fall into the other realms. Our initial inclination was to put the flower in one of these chunks (which make up the “The Last Remnants of Asgard” quest, another of my quests) but our flower model was quite dainty, so it didn’t make sense to us that the flower would fall hundreds of miles to the ground and still be intact.

We then moved our search to “The Broken Prison”, a prison of Asgard that had fallen into the Niflheim region. It made more sense to us that the flower could survive the fall if it fell within a huge building, but we still needed a justification as to why the flower was inside the prison. After looking through the prison, we saw that there was a corpse in an empty cell. We thought it would be poetic for this unnamed character to dedicate the last of his life to take care of this flower, so we placed the Asgard flower next to his corpse and wrote some dialogue that told that story.

The Asgard Flower. The corpse can be seen beside Kratos’s head.

The Jotunheim flower was trickier because Jotunheim was written to be an elusive place in the God of War universe. When I joined the project, Kratos and Freya (who serves as the player’s companion in the postgame) were never supposed to visit Jotunheim at all. When the game’s lore did not give a good reason to justify the flower growing in another realm, Anthony Burch and I began to investigate other characters related to Jotunheim. Of the few characters associated with Jotunheim, only Faye, Kratos’s deceased wife, found her way into other realms like Midgard and Vanaheim. After conferring with the narrative team, we decided to put the flower in Kratos’s and Atreus’s backyard.

The problem then was that there was lot of key banter around the house in the first half of the game, so we couldn’t put the flower there for fear of banter overlap. Eventually, we were able to solve this by having the dialogue reflect that Faye had planted the seed for the flower a long time ago but it did not have the chance to sprout until Ragnarök arrived at the end of the game. Ultimately, we decided not to go in this direction because it was decided that Kratos and Freya should be able to visit Jotunheim in the post-game, but I’m proud of the solution we found.

The Jotunheim flower was ultimately placed in the optional postgame Jotunheim area.

Nuts and Bolts

Towards the end of the project, I was assigned to help finish the work that had started on Ratatoskr and the game’s three dwarven shopkeepers (Brok, Sindri, and Lunda). This involved ensuring that these four characters could give Kratos their respective quests. I also had to ensure that these characters would react accordingly to the events of the main campaign and the specific side content that the player had embarked on. In many ways, this was the most complex task I was assigned because between these characters there were thousands of lines of dialogue, some of which had very specific requirements.

To give you an idea of how specific these requirements got, I had to program a specific line Ratatoskr would say if Brok had died recently, the player has gathered only one lindwyrm, and they had not yet started the “Stag for All Seasons” quest. Making sure these lines played at the correct time required me to know the game’s story and side quests intimately. I had to visualize all the different paths that the player could take before encountering these characters.

Ratatoskr, voiced by the awesome ProZD. Fun fact, I had watched a video by ProZD the day I got the call confirming that I had been hired to work on God of War: Ragnarök.

In addition to making sure that the correct line would play at the right time, I had to make sure that the character speaking the line would be playing the correct animation. For many of these conversations, I hand-programmed what or who each character would be looking at and, in some cases, programmed minor animations or gestures to play on the speaking character to add life to the conversation. Since there were hundreds of lines each with their own set of prerequisites and animations, this led to some odd bugs. For example, there was a point in production where Brok was mysteriously speaking lines of dialogue after he had passed away in the story. We found that this was happening because the banter system had found his resting corpse within the scene and was playing lines out of his rig’s mouth. Thankfully, most bugs were not so haunted.

After these more technical bugs were sorted, my attention turned to bugs that were more about narrative continuity. Since there were hundreds of lines each with varying levels of emotion and tone, part of my job was identifying where lines could combine (however unlikely) to create an experience that broke immersion. For example, Ratatoskr had several lines where he mourned the loss of Brok and also many lines full of innuendo. We couldn’t have those back-to-back. I poured over spreadsheets with Orion Walker, Ratatoskr’s writer, for hours to identify these tonal conflicts and rescript our dialogue system to avoid them. While it was hard work, I believe it led players to feel these characters had a level of interiority. I’m particularly proud that the YouTuber VideoGameDunkey ended his glowing video review of God of War: Ragnarok with some footage of Ratatoskr reacting to the player hitting the chime over and over.

Thank you for allowing me to share some of my process as a Systems and Quest Designer with you. All the work described above was a team effort between the studio’s many talented designers, producers, artists, writers, directors, and QA personnel. I’m proud of the work that our team did.

In the future, I may write more essays about what it means to be a Systems Designer in a AAA context and talk more about some of the other content I worked on in God of War: Ragnarök.